This is an interesting puzzle inspired by Christian Freeling's tile set The China Cube. As it really has nothing to do with China, I call it the Hanging Gardens Problem. Imagine each cube as a section of the Garden, and connections to other cubes are paths and stairways.1

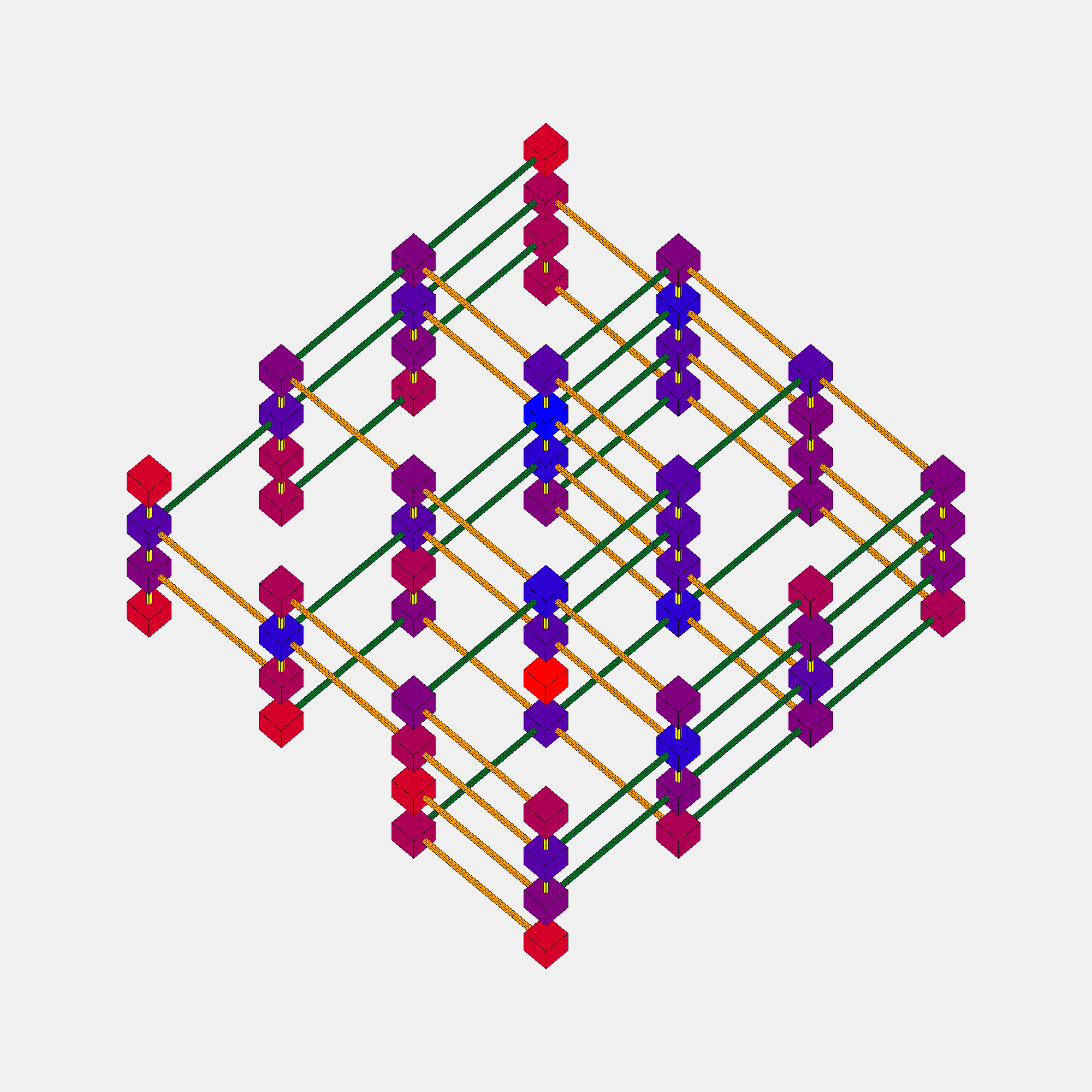

Here is a nice drawing showing the full set of 64 Cubes, from Freeling's site.

Problem Formulation

- There are 64 cubes.

- Each cube is unique.

- Each cube has a specific number of Red and Blue faces.

- Cubes do not rotate or change orientation in anyway.

- Direction of the faces is specific: North, East, South, West, Top, Bottom.

It follows from these that there is

- One cube with all Red faces (the Red cube, bottom Cube in the earlier drawing.)

- One cube with all Blue faces (the Blue cube, top Cube in the earlier drawing)

- Six cubes with one Red face.

- Six cubes with one Blue face.

- ... etc.

All possible permutations of Red and Blue faces are represented (hence 64 cubes).

Here is the puzzle: Assemble the cubes so the Blue faces touch each other, and all the Red faces are exposed.2

In other words, a Blue face must always face, touching, another Blue face. A Red face must not do that. However, a Red face might wave to another Red face from a distance (at least one cube far.)

There is most likely is a solution.

The solution does not have to be one big shape. It actually cannot, because of the Red Cube.

tl;dr I gave up on the problem due to time and memory constraints. However, while I was at it, I found solutions to two, equally interesting, sub problems, and nice graphics.

Wave Function Collapse

I asked around in a number of Discord servers on how to approach solving the problem programmatically, outside of 3-D printing the set and physically assembling it by hand. The Gorilla Sun Creative Coding server suggested that using the Wave Function Collapse algorithm might be the best fit for the problem, and suggested a very excellent Youtube video from the Coding Train implementing the algorithm in Javascript. It is a very good video that I suggest watching.

As explained at the start of the video, this is simply the Sudoku solving algorithm, generalized to creating random tile sets. Apparently, the Quantum Mechanics inspired name is simply for flavor and searchability.

So, how does one solve a Sudoku?

- First, identify the connection rules and the tile set. (Which, in Sudoku, need no explaining.)

- Second, Observation: mark each empty cell in the grid with the candidate

tilesnumbers that go in them. - Third, the Collapse in Wave Function Collapse: identify the cells with the fewest number of candidates. 1. Any cell with 1 candidate "collapses" into that candidate, and the number is inked in. 2. If there are not any cells with one candidate, pick one cell with the fewest number of candidates and pick a candidate at random, "collapsing" it.3

- Fourth, Propagation: with the new state of things, update the candidates in each call. Here is where Sudoku people use X-wings and Swordfishes and what have you.

- Repeat the Collapse, until the grid is full.

- If there ever, after Propagation, a cell with zero candidates, this means an illegal state was reached. Either Backtrack to the last random choice, (and, well, choose another branch), or simply start the whole thing over.

This approach can work just fine for the Hanging Gardens. The Tile set and the connection rules are clearly defined. It is only a matter of putting it into code and .. running it. The problem most apparent to me, however, is that the search space is potentially huge. So, I first need to try this approach with a smaller problem set.

Square Gardens

Phrasing the problem in terms of Squares, and 2D connections, rather than Cubes, shrinks the problem space by an order of magnitude. Plus, there is a known solution given by Freeling!

Tiles and Air

First, I need to formulate the tiles. There are two kinds of Tiles. The first kind is the actually Squares. This is a finite set. The second kind, is an "Air" tile. This empty tile is infinitely available, and is automatically placed at the Propagation phase connected to every Red face. A Red face must connect to an Air tile, and a Blue face can never connect to one. An Air tile can connect from any side to any Air tile with no restriction.

I am still having fun with Odin, so I will try this solution in it first. Here are the starting types:

Side :: enum { North, East, South, West }

Tile :: distinct bit_set[Side]

Air :: distinct struct {}

Cell :: union { Air, Tile }

I am not too happy about this because while the data can neatly fit into one byte, Odin puts this in two. This looks cleaner and easier to understand than weird hacks, so I will stick to it for the time being. Odin's union is nice here, semantically, as it actually has three states: nil, Air and Tile, exactly as much as needed.

The Squares are only 16 (count them in the image above). It is possible to safely ignore the Red (unconnected) Square, because it can simply be put anywhere in space and does not need to connect to anything. Generating a list of the Squares is as simple as counting to 15, or 0xF. Running the below snippet to confirm:

main :: proc () {

list : [dynamic]Cell

for i in u8(0x1) ..= 0xF {

fmt.println(transmute(Tile)i)

append(&list, transmute(Tile)i) // <-- Odin casting magic here

}

fmt.println(len(list))

}

Prints the following:

Tile{North}

Tile{East}

Tile{North, East}

Tile{South}

Tile{North, South}

Tile{East, South}

Tile{North, East, South}

Tile{West}

Tile{North, West}

Tile{East, West}

Tile{North, East, West}

Tile{South, West}

Tile{North, South, West}

Tile{East, South, West}

Tile{North, East, South, West}

15

Which is exactly what is needed. Hooray!!

Grid and Candidates

An infinite grid is infeasible due to being in a finite universe and using computers with finite resources. So what is a good size for a finite grid? There are 16 Tiles, so a 16 by 16 grid is a clear upper bound, and clearly too big, due to the impossibility of all squares being in one line. I will go with a 15 by 15 grid, which is also safe as it is too big, but it gives me a nice center cell to fix the Blue square in, and branch everywhere from there.

To track the candidates in each cell, the simplest option, perhaps, is to create a set of tiles. Since each tile corresponds neatly to a number (as per the transmute above,) simply tracking the numbers should be enough. As mentioned also, the Red square can be placed anywhere in space, so it does not need to be tracked. Giving its number, 0, to track the Air Tile should be enough, as it can later replace almost any Air tile in the final grid.

Candidates :: distinct bit_set[0..=15; u16]

Grid :: struct {

cells: [15][15]Cell, // central cell is [7][7]

candidates: [15][15]Candidates

}

Having candidates in a separate field like that is convenient. Any cell with no candidates (a nil bit set), would signal an illegal position reached. Any cell with only one candidate is considered collapsed, and the collapse would then be reflected in the cells field, which represents the actual contents. All this, of course, is subject to be iterated out later.

This is the first draft of how to initialize the grid. Note that in Odin ~ is the bitwise NOT operator. So ~Candidates{15} is the full set except for 15. And ~Tile{} is the full set.

grid_init :: proc() -> (ret: Grid) {

// Blue Square

ret.cells[7][7] = ~Tile{}

// Fill the Candidates Grid

ret.candidates = ~Candidates{15} // broadcast magic

ret.candidates[7][7] = {15}

return ret

}

Propagation

An astute Sudoku solver would quickly be able to see that this initial list of candidates is, in fact, useless and incorrect. Yes it removes the placed Tile from all candidate positions, but it does not take into account the placed Tile's connections.4 For this to work the Candidate grid must be updated to match the new reality.

It follows that for each placed Cell in cells, it must update the surrounding candidates. So a function that gives out the candidates per face is needed. This can almost just be hardcoded, since each number maps neatly to a specific square. It is possible to hardcode it for each tile individually, but where is the fun in that.

Candidate_Set :: [Side]Candidates // Enumerated arrays, a nice Odin feature.

tile_connections :: proc (c: Cell) -> (ret: Candidate_Set) {

// Why not just hardcode it all the way?

switch t in c {

case Tile:

ret[.North] = {4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15} if .North in t else {0}

ret[.East] = {8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15} if .East in t else {0}

ret[.South] = {1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15} if .South in t else {0}

ret[.West] = {2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 15} if .West in t else {0}

case Air:

ret[.North] = {0, 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11}

ret[.East] = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}

ret[.South] = {0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14}

ret[.West] = {0, 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13}

case:

ret = ~{}

}

return

}

This is nice, mainly because the Candidates type, being a bit set, can be ANDed together to quickly eliminate candidates from Cells in the relevant direction. This can be run for each new state in a loop (or maybe just twice) to propagate candidates of collapsed Air Cells.

The grid_propagate procedure will have to do a few things. First, it should scan cells for known placements. If there is a known placement, update candidates accordingly. Then scan candidates for any collapsed cells (where there is only one left candidate), and update those in cells accordingly, then repeat. Assertions could be placed if a known placement in cells does not match a collapsed candidates set in candidates. An error would be returned if, during propagation, a candidates cell was found with 0 candidates, indicating an illegal branch reached.

After some trial and error and stack overflows and segmentation faults (due to said stack overflows), I settled on this recursive version It is probably not efficient, as it calculates the same thing multiple times, but it is the most straightforward way i could think of.

grid_propagate :: proc (grid: ^Grid) -> bool {

// Update candidates based on cells

for y in 0..<15 do for x in 0..<15 {

cell := grid.cells[x][y]

tc := tile_connections(cell)

// North

if y < 14 do grid.candidates[x][y + 1] &= tc[.North]

// East

if x < 14 do grid.candidates[x + 1][y] &= tc[.East]

// South

if y > 0 do grid.candidates[x][y - 1] &= tc[.South]

// West

if x > 0 do grid.candidates[x - 1][y] &= tc[.West]

// if cell is a tile, make sure it is not a candidate anywhere else.

if tile, ok := cell.(Tile); ok {

// Weird hack

cand := Candidates{ int(transmute(u8)tile) }

// remove it everywhere with broadcast magic

grid.candidates -= cand

// then add it in the appropriate place

grid.candidates[x][y] = cand

}

}

any_collapsed := false

// Update cells based on candidates

for y in 0..<15 do for x in 0..<15 {

cand := grid.candidates[x][y]

if cand == {} do return false // illegal state reached

// COLLAPSE

// obviously only a new collapse if it is not collapsed already

if grid.cells[x][y] == nil && card(cand) == 1 do for id in cand {

any_collapsed = true

// What did actually collapse

grid.cells[x][y] = Air{} if id == 0 else transmute(Tile)i8(id)

}

}

success := true

if any_collapsed do success = grid_propagate(grid) // recursion!!

return success

}

Then just update grid_init like this

grid_init :: proc () -> (ret: Grid) {

// Fill the Candidates Grid

ret.candidates = ~Candidates{}

// Place Blue square

ret.cells[7][7] = ~Tile{}

grid_propagate(&ret)

return ret

}

And it works, nicely! Place any of the Squares instead of ~Tile{}, and it works correctly. Even propagates Air cells and their neighbors!!

Controlled Demolition

The grid_propagate procedure takes of care of collapsing cells with one candidate left. But as soon as right after the initial position, there are still many cells with unresolved state. That's why Controlled Demolition is needed, to force things to collapse, randomly.5

The best candidates for Controlled Demolition are the cells with the least amount of candidates that are not already collapsed. That's to say, the least amount of candidates more than 1. Recording these is probably easy. Choosing one randomly, with even chances all over, is, at first impression, not. It is easy to choose arbitrarily, but not necessarily randomly. If a robust backtracking algorithm exists, then arbitrary is probably better than random. But I do not currently plan to backtrack, but instead simply start over whenever an illegal position is encountered.

How should one go about this? With so much randomness, the probably most straightforward course of action is to randomize the indices 0-14 three times. The first two randomized arrays are to loop over candidates in a somewhat random order. The third one is to loop over the candidates in the final found cell, and collapse to the first one it matches over.

Sounds absolutely boneheaded, but it should work just fine.

grid_controlled_demolition :: proc (grid: ^Grid) -> bool {

// all the shuffling

rows := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 }

rand.shuffle(rows)

cols := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 }

rand.shuffle(cols)

ids := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 }

rand.shuffle(ids)

// target collapse stored here

t_x, t_y: int

// tracking the minimum

min_card := 15

// loop over the grid "randomly"

for y in cols do for x in rows {

c := card(grid.candidates[x][y])

(c > 1) or_continue // already collapsed

if c < min_card {

t_x = x

t_y = y

min_card = c

}

if min_card == 2 do break // no point in looking further

}

// loop over the set flags randomly and collapse to the first match.

for id in ids do if id in grid.candidates[t_x][t_y] {

// COLLAPSE

if id == 0 {

grid.cells[t_x][t_y] = Air{}

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y] = {0}

} else {

tile := transmute(Tile)i8(id)

cand := Candidates{ int(transmute(u8)tile) }

grid.cells[t_x][t_y] = tile

grid.candidates -= cand

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y] = cand

}

break

}

// then propagate the new changes, returning the legality result

return grid_propagate(grid)

}

This should be enough? Calling grid_controlled_demolition a couple of times seems to produce the expected result.

main :: proc () {

grid := grid_init()

// crude

grid_controlled_demolition(&grid)

grid_controlled_demolition(&grid)

grid_controlled_demolition(&grid)

grid_controlled_demolition(&grid)

grid_controlled_demolition(&grid)

for row, ri in grid.candidates do for c, ci in row {

fmt.println(ri, ci, c)

}

}

Sample output.

0 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

0 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

1 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

2 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

3 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

4 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 8 Candidates{0, 1, 4, 8, 12}

5 9 Candidates{2, 3, 7, 10, 11}

5 10 Candidates{2, 3, 7, 10, 11}

5 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

5 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 7 Candidates{0, 2, 4, 8, 10, 12}

6 8 Candidates{0}

6 9 Candidates{9}

6 10 Candidates{13}

6 11 Candidates{4, 7, 12}

6 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

6 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 7 Candidates{1, 3, 7, 11}

7 8 Candidates{6}

7 9 Candidates{0}

7 10 Candidates{0}

7 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 8, 10, 11}

7 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

7 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 7 Candidates{1, 3, 7, 11}

8 8 Candidates{15}

8 9 Candidates{5}

8 10 Candidates{4, 7}

8 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

8 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 7 Candidates{1, 3, 7, 11}

9 8 Candidates{14}

9 9 Candidates{0}

9 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 8, 10, 11}

9 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

9 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 8 Candidates{8, 10, 11, 12}

10 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7}

10 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

10 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

11 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

12 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

13 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 0 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 1 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 2 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 3 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 4 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 5 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 6 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 7 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 8 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 9 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 10 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 11 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 12 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 13 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

14 14 Candidates{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12}

Success and Failure

This seems to work fine. But it is still missing one thing: it needs to know when to stop. If it is a successful solution, (where every cell has exactly one candidate), then stop and print it out. If it is a failed solution, try again. Thankfully, this could be expressed in a couple of lines, with the assumption that the grid has collapsed completely if the first element in the grid, as unlikely as it is to be reached, equals {0}, an Air cell.:

main :: proc () {

grid := grid_init()

outer: for {

for grid_controlled_demolition(&grid) {

if grid.candidates[0][0] == {0} do break outer

}

grid = grid_init()

}

grid_print(&grid) // uninteresting code. it is a grid.

}

Here are two sample results, which appear to be correct. The second result is interesting as it has a floating element. Obviously the code is undeterministic: each time it runs it gives a different result.6

// try 1

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |02| | | | | | |

| | | | | | |03|07|12| | | | | | |

| | | | | | |11|14| | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |09|15|04| | | | | | |

| | | | | | | |10| | | | | | | |

| | | | | |01|05|13|06| | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | |08| | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

// try 2

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |01|06| |02| | | | | |

| | | | | | | |10| |08| | | | | |

| | | | | | |03|14| | | | | | | |

| | | | | | |11|15|07|05|04| | | | |

| | | | | | |09|13|12| | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

3D Cubes here I come!!

Packed Gardens

As the solution for the Square Gardens works, it is obvious that simply changing the data structures and the hardcoded values would solve the 3D solution. I will get to that, but first, I want to try a Packed solution first.

The Packed solution has a much simpler to state goal: Pack all 64 cubes into a 4x4x4 cube. Obviously, in this version, the Red faces can (actually have to) face each other. Only Red faces are allowed to face outside. In his page about the set, Freeling does actually provide one Packed solution, with a caveat.

The caveat here is that the Red Cube must be contained inside, and not on the edge. It is a difficult requirement, but the provided solution achieves it, at the cost of another floating group at the bottom left of the image above.

Initialization

Nonetheless, as it is only a 4x4x4 cube, the search space for the solution is much smaller. There are no Air tiles in here: it is packed. Adding the additional requirement of the Red Cube being wholly contained actually simplifies the solution's initialization. Start the Blue cube at (1,1,1) coordinates, and the Red cube at (2,2,2) coordinates. Any other placement of the two Cubes would actually be a mirror image, or a rotation, of this specific arrangement.

Here are the types, which, for the most part, are shared between the Packed Gardens and the Hanging Gardens, and the initialization function as described.

Side :: enum u8 { North, East, South, West, Top, Bottom }

Tile :: distinct bit_set[Side; u8]

Cell :: Maybe(Tile)

Candidates :: distinct bit_set[0..<64; u64]

Grid :: struct {

cells: [4][4][4]Cell,

candidates: [4][4][4]Candidates,

}

Candidate_Set :: [Side]Candidates

grid_init :: proc () -> (ret: Grid) {

// Fill the candidate Grid

ret.candidates = ~Candidates{ 0, 63 }

// Place Blue and Red cubes respectively

ret.cells[1][1][1] = ~Tile{}

ret.cells[2][2][2] = Tile{}

// Placeholder for now

grid_propagate(&ret)

return

}

Cube Edges

Unlike in the Square Gardens, this is not enough. While the candidates for the edges were safely ignored there, (as the the solution is unlikely to reach them), they must be encoded here, because they are integral. Time to hardcode the implementation! This is how the values are generated:

generate_consts :: proc () {

for side in (~Tile{}) {

fmt.printf("%v_CONNECTED :: Candidates{{", side)

for i in 0..<64 {

tile := transmute(Tile)u8(i)

if side in tile do fmt.print(i, ",")

}

fmt.println("}")

fmt.printf("%v_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{{", side)

for i in 0..<64 {

tile := transmute(Tile)u8(i)

if side not_in tile do fmt.print(i, ",")

}

fmt.println("}")

}

}

And this is the generated code (with light formatting editing). I have no idea if it is correct. The proof of the pudding is in the eating.

NORTH_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 51, 53, 55, 57, 59, 61, 63 }

EAST_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 22, 23, 26, 27, 30, 31, 34, 35, 38, 39, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 51, 54, 55, 58, 59, 62, 63 }

SOUTH_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 30, 31, 36, 37, 38, 39, 44, 45, 46, 47, 52, 53, 54, 55, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

WEST_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

TOP_CONNECTED :: Candidates{16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

BOTTOM_CONNECTED :: Candidates{32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

NORTH_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 60, 62 }

EAST_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29, 32, 33, 36, 37, 40, 41, 44, 45, 48, 49, 52, 53, 56, 57, 60, 61 }

SOUTH_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18, 19, 24, 25, 26, 27, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 43, 48, 49, 50, 51, 56, 57, 58, 59 }

WEST_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 }

TOP_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 }

BOTTOM_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 }

tile_connections :: proc (c: Cell) -> (ret: Candidate_Set) {

switch t in c {

case Tile:

ret[.North] = .North in t ? SOUTH_CONNECTED : SOUTH_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.East] = .East in t ? WEST_CONNECTED : WEST_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.South] = .South in t ? NORTH_CONNECTED : NORTH_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.West] = .West in t ? EAST_CONNECTED : EAST_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.Top] = .Top in t ? BOTTOM_CONNECTED : BOTTOM_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.Bottom] = .Bottom in t ? TOP_CONNECTED : TOP_NOT_CONNECTED

case:

ret = ~{}

}

return

}

Then edit grid_init to adjust the candidates in the edge cubes accordingly. However, care must be taken as how these values translate there. For example, the westernmost cubes are the ones that do not have a connection on the .West side. Again, I am not currently sure how correct this is. The pudding is yet to be eaten.

grid_init :: proc () -> (ret: Grid) {

// Fill the candidate Grid

ret.candidates = ~Candidates{ 0, 63 }

for z in 0..<4 do for y in 0..<4 do for x in 0..<4 {

if x == 0 do ret.candidates[x][y][z] &= WEST_NOT_CONNECTED

if x == 3 do ret.candidates[x][y][z] &= EAST_NOT_CONNECTED

if y == 0 do ret.candidates[x][y][z] &= SOUTH_NOT_CONNECTED

if y == 3 do ret.candidates[x][y][z] &= NORTH_NOT_CONNECTED

if z == 0 do ret.candidates[x][y][z] &= BOTTOM_NOT_CONNECTED

if z == 3 do ret.candidates[x][y][z] &= TOP_NOT_CONNECTED

}

// Place Blue and Red cubes respectively

ret.cells[1][1][1] = ~Tile{}

ret.cells[2][2][2] = Tile{}

// still a placeholder

grid_propagate(&ret)

return

}

Propagation and Controlled Demolition

Applying minor changes from the Square Gardens' grid_propgagate and grid_controlled_demolition, they end up like this.

grid_propagate :: proc (grid: ^Grid) -> bool {

// Update candidates based on cells

for z in 0..<4 do for y in 0..<4 do for x in 0..<4 {

cell := grid.cells[x][y][z]

tc := tile_connections(cell)

if y < 3 do grid.candidates[x][y + 1][z] &= tc[.North]

if x < 3 do grid.candidates[x + 1][y][z] &= tc[.East]

if y > 0 do grid.candidates[x][y - 1][z] &= tc[.South]

if x > 0 do grid.candidates[x - 1][y][z] &= tc[.West]

// Top

if z < 3 do grid.candidates[x][y][z + 1] &= tc[.Top]

// Bottom

if z > 0 do grid.candidates[x][y][z - 1] &= tc[.Bottom]

if tile, ok := cell.(Tile); ok {

// Weird magic

cand := Candidates{ int (transmute(u8)tile) }

grid.candidates -= cand

grid.candidates[x][y][z] = cand

}

}

any_collapsed := false

// Update cells based on candidates

for z in 0..<4 do for y in 0..<4 do for x in 0..<4 {

cand := grid.candidates[x][y][z]

if cand == {} do return false

if grid.cells[x][y][z] == nil && card(cand) == 1 do for id in cand {

any_collapsed = true

grid.cells[x][y][z] = transmute(Tile)u8(id)

}

}

success := true

if any_collapsed do success = grid_propagate(grid) // recursion!!

return success

}

grid_controlled_demolition :: proc (grid: ^Grid) -> bool {

// all the shuffling

rows := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3 }

rand.shuffle(rows)

cols := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3 }

rand.shuffle(cols)

verts := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3 }

rand.shuffle(verts)

ids := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15,

16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31,

32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47,

48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63}

rand.shuffle(ids)

t_x, t_y, t_z: int

min_card := max(int)

for z in verts do for y in cols do for x in rows {

c := card(grid.candidates[x][y][z])

(c > 1) or_continue

if c < min_card {

t_x = x

t_y = y

t_z = z

min_card = c

}

if min_card == 2 do break

}

for id in ids do if id in grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] {

tile := transmute(Tile)i8(id)

cand := Candidates{ id }

grid.cells[t_x][t_y][t_z] = tile

grid.candidates -= cand

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] = cand

break

}

return grid_propagate(grid)

}

And this does it. Figuring out how to ascertain how every cell in the grid has only one candidate took a bit of finessing and experimenting with Odin's core library slice.all_in_proc, but I ended up doing it manually.

main :: proc () {

grid := grid_init()

outer: for {

inner: for grid_controlled_demolition(&grid) {

for z in 0..<4 do for y in 0..<4 do for x in 0..<4 {

if card(grid.candidates[x][y][z]) != 1 do continue inner

}

break outer

}

grid = grid_init()

}

grid_draw(grid) // <-- this one is a bit more interesting.

}

This works, and thankfully halts. However, the execution time, in the few times I ran it, varied anything between 3 seconds and one minute. This obviously depends on how lucky the random seed is. Using threads would help to get a result faster.

Printing the solution naïvely prints a bunch of numbers, with no repeats (as far I could tell), but to verify that the solution is correct it needs to be outputted into a readable format. THe "easy" solution is to put together a dictionary of images and make a collage, much like the image at the top of the section, but that is not very interesting.

Solution Output

Simply printing out the resultant grid to console is not a very useful output. With the Square Gardens, it is possible to verify the correctness of the result by simply checking, visually, that each number/square is the only one in the grid that has neighbors in a specific configuration.

In other words, look at this grid given from before (with pointless empty spaces removed and the Red Square 00 added):

| | | | | | |

| |00| | |02| |

| | |03|07|12| |

| | |11|14| | |

| | |09|15|04| |

| | | |10| | |

| |01|05|13|06| |

| | | | |08| |

| | | | | | |

It is easy to verify that, for example, 08 is literally the only tile that has only one connection to the top (and whether in code that's North or South is irrelevant to the correctness of the solution.) 14, for example, is the only tile that has only three connections to the top, left, and bottom, and so on for all of them.

For the packed solution, it is harder to verify that over text output. One solution would be to create a little image for every cube, (as Freeling's provided solution does) and pack them together. The other solution is to render a 3D image of the solution and visually inspect it that way.

Looking over Odin's vendor libraries, and asking around for ideas how to do that, I could not figure out how to draw on an image canvas (the way the imageproc lets me do in Rust.) But there are a few bindings to different graphics libraries, and word on the street was that raylib is the simplest solution for this sort of thing.

I spent a day playing around with raylib's tutorials and asking for help on the Discord. The API is ... weirder than I am used to, to say the least. But it looks simple enough. To draw a window with a render scene, the code is the following:

import rl "vendor:raylib"

grid_draw :: proc (grid: Grid) {

SCREEN_WIDTH :: 400

SCREEN_HEIGHT :: 200

// raylib must start with this.

rl.InitWindow(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT, "")

// and end with this.

defer rl.CloseWindow()

camera := rl.Camera3D{

position = ({10.0, -5.0, 5.0} + 2.5),

target = {2.5, 2.5, 2.5},

up = {0.0, 1.0, 0.0},

fovy = 50,

projection = .ORTHOGRAPHIC

}

for !rl.WindowShouldClose() {

rl.UpdateCamera(&camera, .THIRD_PERSON)

// This honestly weird pattern is how everything in raylib must work

rl.BeginDrawing()

defer rl.EndDrawing()

rl.ClearBackground(rl.WHITE)

rl.BeginMode3D(camera)

defer rl.EndMode3D()

// draw 3D things here.

}

}

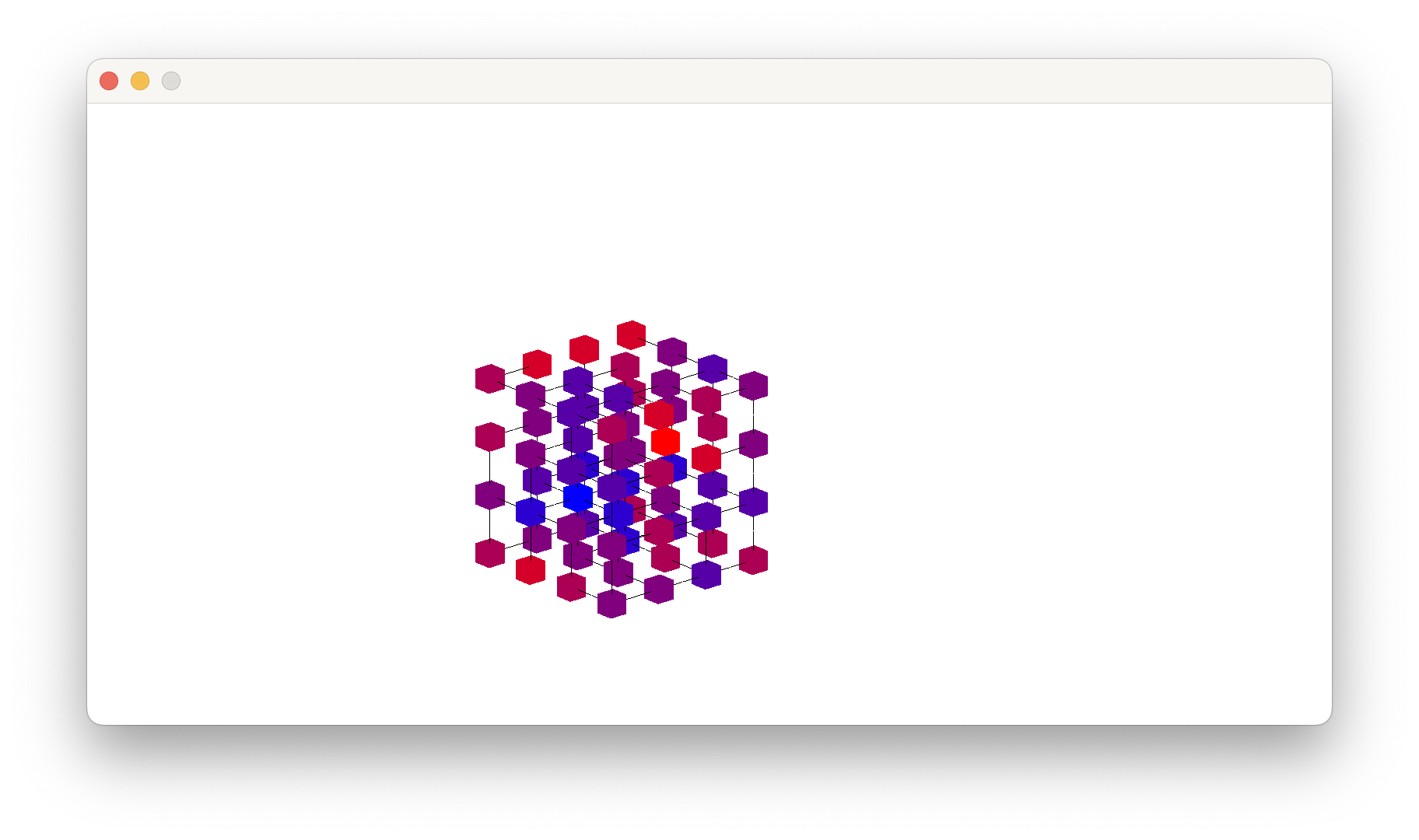

Just to test things out, I will try drawing each cube with a different shade based on how many connections it has. The Blue cube shall be blue and the Red cube shall be red, and the other cubes will be different shades of purple.

for z in 0..<4 do for y in 0..<4 do for x in 0..< 4 {

tile := grid.cells[x][y][z].(Tile) or_continue

grade := u8(card(tile))

b := (max(u8) / 6) * grade

r := max(u8) - b

rl.DrawCubeV({f32(x), f32(y), f32(z)}, 1.0, {r, 0, b, 255})

}

And now: the moment of truth odin run .

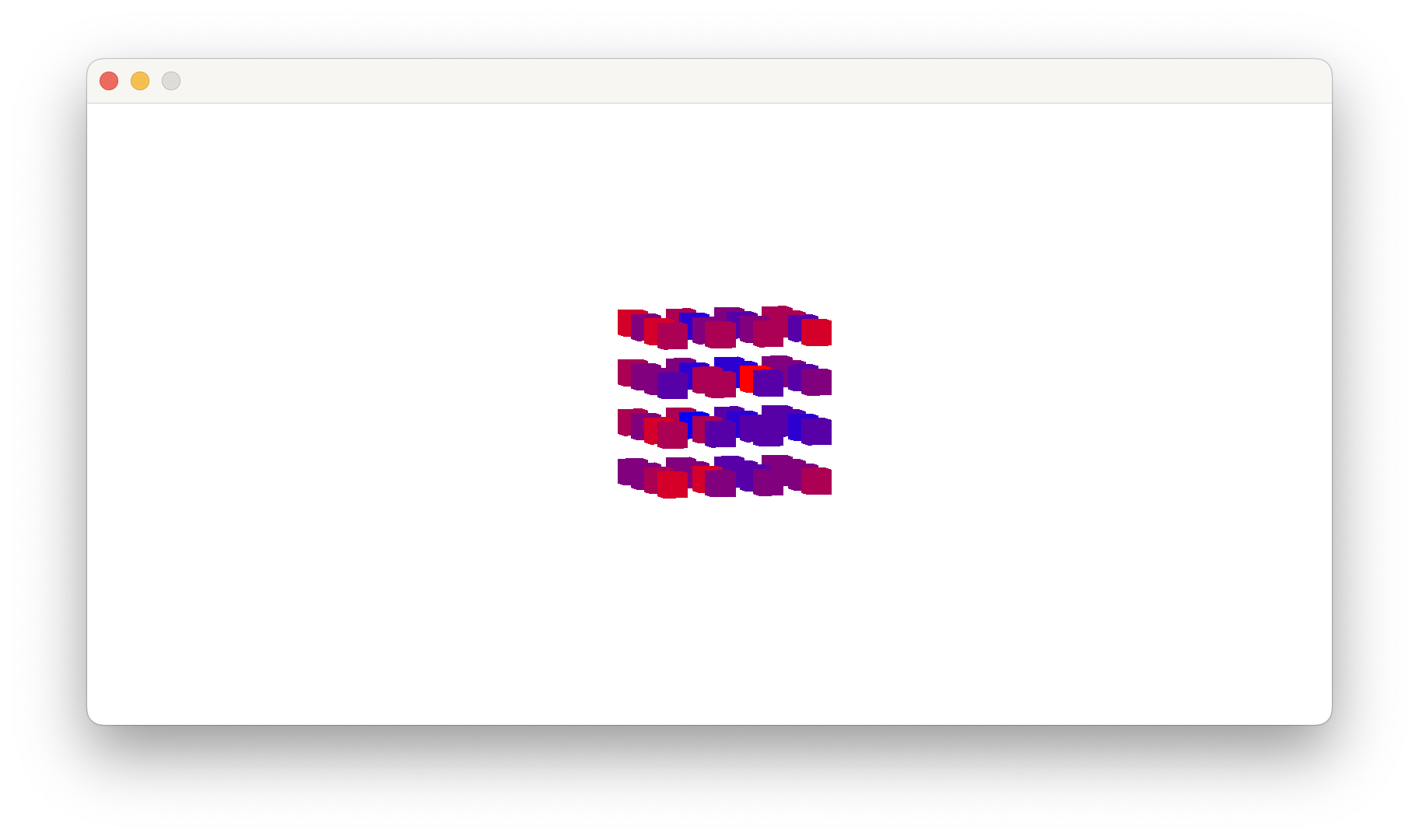

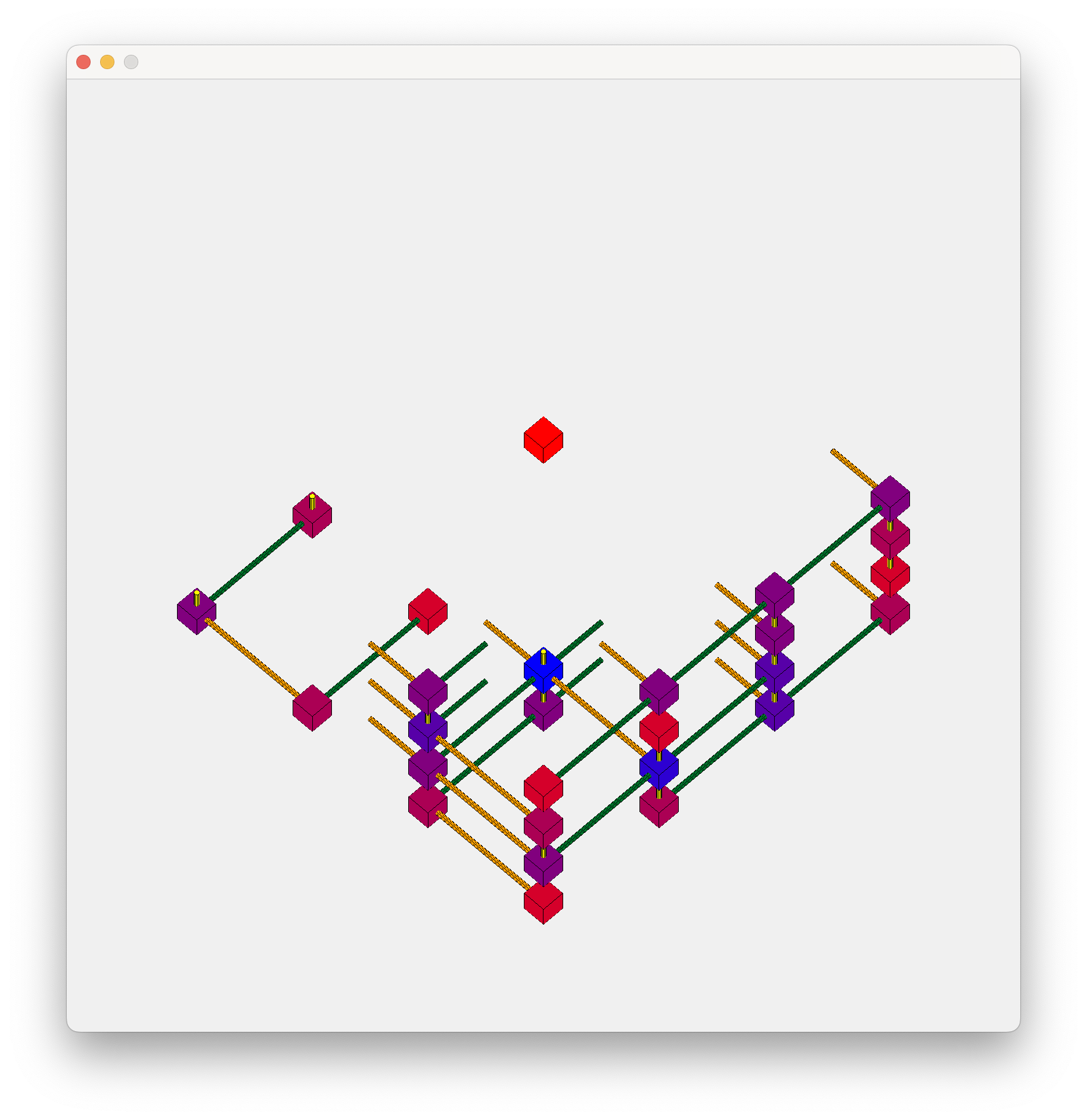

I have no idea what's going on here. Everything is mushed together and the screen is tiny. Upping the screen's resolution (to 800, 400), multiplying the position by 2.0 would be a start, and bringing the camera closer would be a decent start.7

Ah .. much better already. This actually rotates (but not zooms) with the mouse movement, thanks to that .THIRD_PERSON setting up there. Time to draw the lines, and better organize the code while I am at it. Here is the full function. (I do not actually expect this to be correct.)

grid_draw :: proc(grid: Grid) {

SCREEN_WIDTH :: 1200

SCREEN_HEIGHT :: 600

CUBE_DISTANCE :: 3.0

CENTER_POINT :: 2.5 * CUBE_DISTANCE

rl.InitWindow(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT, "")

defer rl.CloseWindow()

camera := rl.Camera3D {

position = ({10.0, -5.0, 5.0} + CENTER_POINT),

target = CENTER_POINT,

up = {0.0, 1.0, 0.0},

fovy = 30,

projection = .ORTHOGRAPHIC,

}

for !rl.WindowShouldClose() {

rl.UpdateCamera(&camera, .THIRD_PERSON)

rl.BeginDrawing()

defer rl.EndDrawing()

rl.ClearBackground(rl.WHITE)

rl.BeginMode3D(camera)

defer rl.EndMode3D()

for z in 0 ..< 4 do for y in 0 ..< 4 do for x in 0 ..< 4 {

tile := grid.cells[x][y][z].(Tile) or_continue

grade := u8(card(tile))

pos := rl.Vector3{f32(x), f32(y), f32(z)} * CUBE_DISTANCE

size := rl.Vector3{ 1.0, 1.0, 1.0 }

b := (max(u8) / 6) * grade

r := max(u8) - b

color := rl.Color{ r, 0, b, 255}

rl.DrawCubeV( pos, size, color )

if .North in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .South in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, -CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .East in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + { CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .West in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {-CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .Top in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, 0, CUBE_DISTANCE / 2}, rl.BLACK)

if .Bottom in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, 0, -CUBE_DISTANCE / 2}, rl.BLACK)

}

}

}

This looks .. ok? half decent? Rotating it around does not show any mistakes. The centering is off, however. And due to the Orthographic projection and camera work I cannot zoom in to see how everything connects in more detail.

Faster Iteration of Visuals

Also, frankly, I am getting tired of waiting for the solution to solve before the render show up, so I am changing the code a bit to, maybe, see the cube solve it in real time. This makes the solver much slower, but it makes for a fun animation.

SCREEN_WIDTH :: 800

SCREEN_HEIGHT :: 800

CUBE_DISTANCE :: 3.0

CENTER_POINT :: 1.5 * CUBE_DISTANCE

main :: proc () {

rl.InitWindow(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT, "")

defer rl.CloseWindow()

rl.SetTargetFPS(60)

camera := rl.Camera3D {

position = ({10.0, -5.0, 5.0} + CENTER_POINT),

target = CENTER_POINT,

up = {0.0, 1.0, 0.0},

fovy = 30,

projection = .ORTHOGRAPHIC,

}

grid := grid_init()

solved := false

paused := false

for !rl.WindowShouldClose() {

rl.UpdateCamera(&camera, .THIRD_PERSON)

if rl.IsKeyPressed(.SPACE) do paused ~= true

{ // Draw current state

rl.BeginDrawing()

defer rl.EndDrawing()

rl.ClearBackground(rl.WHITE)

rl.BeginMode3D(camera)

defer rl.EndMode3D()

for z in 0 ..< 4 do for y in 0 ..< 4 do for x in 0 ..< 4 {

tile := grid.cells[x][y][z].(Tile) or_continue

grade := u8(card(tile))

pos := rl.Vector3{f32(x), f32(y), f32(z)} * CUBE_DISTANCE

size := rl.Vector3{ 1.0, 1.0, 1.0 }

b := (max(u8) / 6) * grade

r := max(u8) - b

color := rl.Color{ r, 0, b, 255}

rl.DrawCubeV( pos, size, color )

if .North in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .South in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, -CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .East in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + { CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .West in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {-CUBE_DISTANCE / 2, 0, 0}, rl.BLACK)

if .Top in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, 0, CUBE_DISTANCE / 2}, rl.BLACK)

if .Bottom in tile do rl.DrawLine3D(pos, pos + {0, 0, -CUBE_DISTANCE / 2}, rl.BLACK)

}

}

if !paused && !solved {

if grid_controlled_demolition(&grid) {

solved = true

for z in 0..<4 do for y in 0..<4 do for x in 0..<4 {

if card(grid.candidates[x][y][z]) != 1 {

solved = false

break

}

}

} else {

grid = grid_init()

solved = false

}

}

}

}

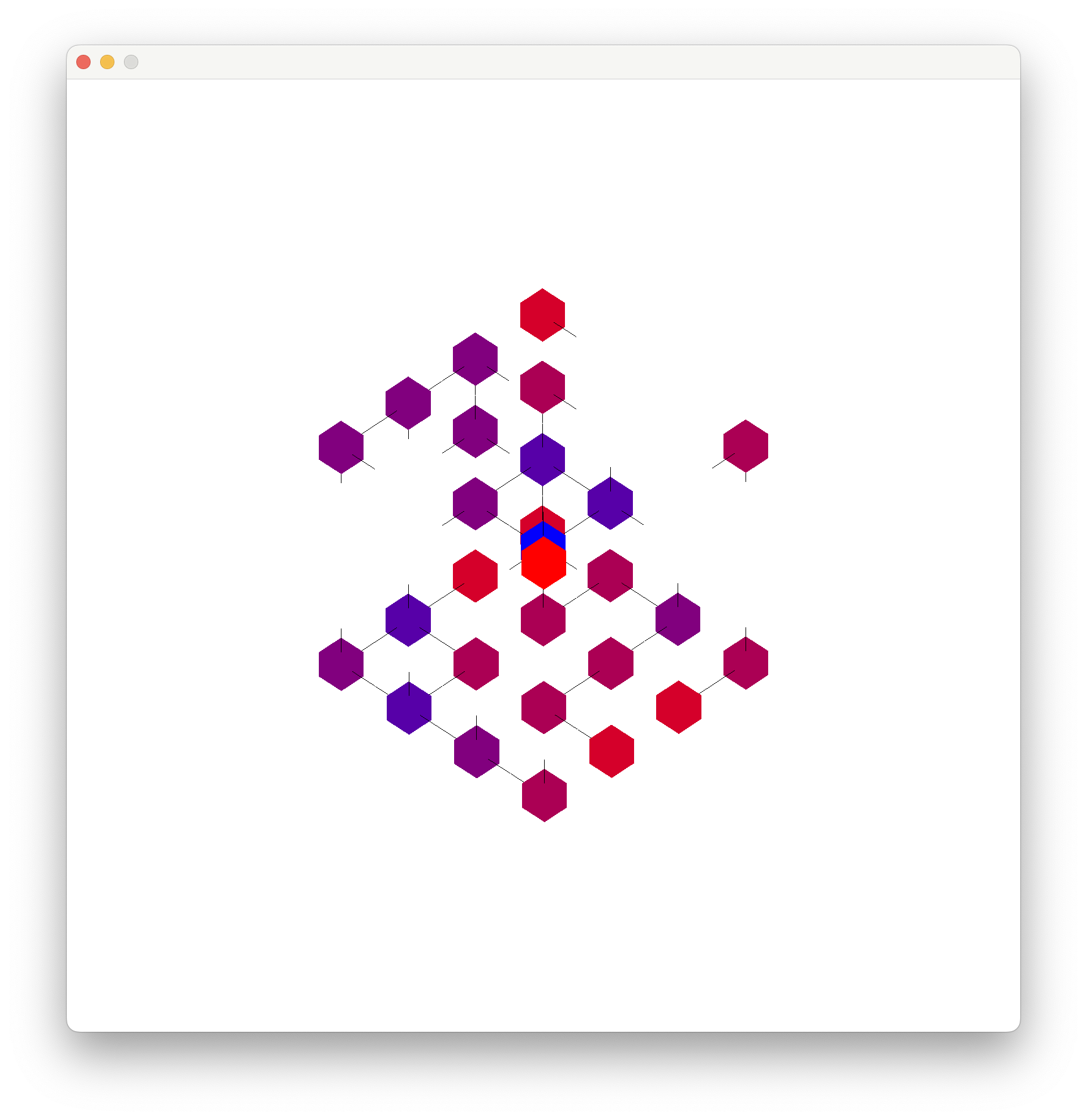

Well this is a lot more pleasant to look at, isn't it? One nicety: it pauses when the Space bar is pressed, easier to inspect the connections. It will find a solution in a million years, but until that happens it would be easier to iterate the presentation's colors and distances.

Miracolously, howver, no matter when I pause it, the connections between adaject cubes are always correct. There are no cubes that are next to each other with one line hanging midways between them. Every high five is reciprocated. This is a fancy screenshot for an attempted solution.

Final Visuals

After a bit of trial and error and experimenting with different colors and distances and camera positions, I ended up with these constants and draw functions.

SCREEN_WIDTH :: 800

SCREEN_HEIGHT :: 800

CUBE_DISTANCE_X :: 6.0

CUBE_DISTANCE_Y :: 6.0

CUBE_DISTANCE_Z :: 2.5

CENTER_POINT :: [3]f32 {

1.5 * CUBE_DISTANCE_X,

1.5 * CUBE_DISTANCE_Y,

1.5 * CUBE_DISTANCE_Z

}

main :: proc () {

// boring boilerplate

camera := rl.Camera3D {

position = ({-7, -7, 15} + CENTER_POINT),

target = CENTER_POINT,

up = {0.0, 0.0, 1.0},

fovy = 35,

projection = .ORTHOGRAPHIC,

}

// other boring boilerplate

rl.ClearBackground(rl.Color{ 240, 240, 240, 255 })

// you know

pos := rl.Vector3{

f32(x) * CUBE_DISTANCE_X,

f32(y) * CUBE_DISTANCE_Y,

f32(z) * CUBE_DISTANCE_Z,

}

// more of it

rl.DrawCubeV(pos, size, color)

rl.DrawCubeWiresV(pos, size, rl.BLACK)

if .North in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, CUBE_DISTANCE_Y / 2, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.ORANGE)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .South in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, -CUBE_DISTANCE_Y / 2, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.ORANGE)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .East in tile {

end_pos := pos + { CUBE_DISTANCE_X / 2, 0, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.DARKGREEN)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .West in tile {

end_pos := pos + {-CUBE_DISTANCE_X / 2, 0, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.DARKGREEN)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .Top in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, 0, CUBE_DISTANCE_Z / 2}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.YELLOW)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .Bottom in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, 0, -CUBE_DISTANCE_Z / 2}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.YELLOW)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

// end of proc boilerplate

}

Producing an Image

Well, now that apparently all the logic and visuals are top notch and as clear as they can be, I do not actually want a visual of the solver solving and taking for ever. I only want a final image. So I will revert main to what it was before, and adjust grid_draw so it only saves an image to disk, rather than opening a window and waiting for me to take a screenshot.

The code is mostly the same as before, only without starting a loop. raylib has functions to render a texture and save it as an image without third party libraries, so I just use those.

This is the final grid_draw and its resultant image

grid_draw :: proc(grid: Grid) {

rl.SetConfigFlags({.WINDOW_HIDDEN})

rl.InitWindow(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT, "")

defer rl.CloseWindow()

camera := rl.Camera3D {

position = ({7, 7, -15} + CENTER_POINT),

target = CENTER_POINT,

up = {0.0, 0.0, 1.0},

fovy = 35,

projection = .ORTHOGRAPHIC,

}

txtr := rl.LoadRenderTexture(SCREEN_WIDTH, SCREEN_HEIGHT)

{ // Drawing here

rl.BeginTextureMode(txtr)

defer rl.EndTextureMode()

rl.BeginDrawing()

defer rl.EndDrawing()

rl.ClearBackground(rl.Color{ 240, 240, 240, 255 })

rl.BeginMode3D(camera)

defer rl.EndMode3D()

for z in 0 ..< 4 do for y in 0 ..< 4 do for x in 0 ..< 4 {

tile := grid.cells[x][y][z].(Tile) or_continue

grade := u8(card(tile))

pos := rl.Vector3{

f32(x) * CUBE_DISTANCE_X,

f32(y) * CUBE_DISTANCE_Y,

f32(z) * CUBE_DISTANCE_Z

}

size := rl.Vector3{1.0, 1.0, 1.0}

b := (max(u8) / 6) * grade

r := max(u8) - b

color := rl.Color{r, 0, b, 255}

rl.DrawCubeV(pos, size, color)

rl.DrawCubeWiresV(pos, size, rl.BLACK)

if .North in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, CUBE_DISTANCE_Y / 2, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.ORANGE)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .South in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, -CUBE_DISTANCE_Y / 2, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.ORANGE)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .East in tile {

end_pos := pos + {CUBE_DISTANCE_X / 2, 0, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.DARKGREEN)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .West in tile {

end_pos := pos + {-CUBE_DISTANCE_X / 2, 0, 0}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.DARKGREEN)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .Top in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, 0, CUBE_DISTANCE_Z / 2}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.YELLOW)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

if .Bottom in tile {

end_pos := pos + {0, 0, -CUBE_DISTANCE_Z / 2}

rl.DrawCylinderEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.YELLOW)

rl.DrawCylinderWiresEx(pos, end_pos, 0.1, 0.1, 12, rl.BLACK)

}

}

}

img := rl.LoadImageFromTexture(txtr.texture)

rl.ExportImage(img, "result.png")

}

Hanging Gardens

With the Square Gardens and the Packed Gardens done, time to return to the original problem. Much of the different pieces of the solution are already in place, and it is just a question of assembling them together.

The main problem left is how to determine the proper size of the grid. It needs to be big enough to potentially accept any variation of the problem, but small enough that it does not cause a stack overflow. When I was experimenting with it, I tried a grid of size 31x31x31 and the Odin compiler warnned8 me that it is so big it might cause said overflow. Or might just put it on the heap and let the OS take care of cleaning it from memory.

Frankenstein's Monster

This is the full program, with a helpful GRID_SIZE constant that allowed me to iterate and debug a bit with a smaller grid size.

package hanging_gardens

import "core:fmt"

import "core:math/rand"

GRID_SIZE :: 31

MID_POINT :: (GRID_SIZE - 1) / 2

Side :: enum u8 { North, East, South, West, Top, Bottom }

Tile :: distinct bit_set[Side; u8]

Air :: distinct struct {}

Cell :: union { Air, Tile }

Candidates :: distinct bit_set[0..<64; u64]

Grid :: struct {

cells: [GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE]Cell,

candidates: [GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE]Candidates,

}

Candidate_Set :: [Side]Candidates

NORTH_CONNECTED :: Candidates { 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 19, 21, 23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 33, 35, 37, 39, 41, 43, 45, 47, 49, 51, 53, 55, 57, 59, 61, 63 }

EAST_CONNECTED :: Candidates { 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 11, 14, 15, 18, 19, 22, 23, 26, 27, 30, 31, 34, 35, 38, 39, 42, 43, 46, 47, 50, 51, 54, 55, 58, 59, 62, 63 }

SOUTH_CONNECTED :: Candidates { 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 14, 15, 20, 21, 22, 23, 28, 29, 30, 31, 36, 37, 38, 39, 44, 45, 46, 47, 52, 53, 54, 55, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

WEST_CONNECTED :: Candidates { 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

TOP_CONNECTED :: Candidates {16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

BOTTOM_CONNECTED :: Candidates {32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

NORTH_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 22, 24, 26, 28, 30, 32, 34, 36, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 60, 62 }

EAST_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 4, 5, 8, 9, 12, 13, 16, 17, 20, 21, 24, 25, 28, 29, 32, 33, 36, 37, 40, 41, 44, 45, 48, 49, 52, 53, 56, 57, 60, 61 }

SOUTH_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18, 19, 24, 25, 26, 27, 32, 33, 34, 35, 40, 41, 42, 43, 48, 49, 50, 51, 56, 57, 58, 59 }

WEST_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 }

TOP_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47 }

BOTTOM_NOT_CONNECTED :: Candidates{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31 }

tile_connections :: proc (c: Cell) -> (ret: Candidate_Set) {

switch t in c {

case Tile:

ret[.North] = SOUTH_CONNECTED if .North in t else {0}

ret[.East] = WEST_CONNECTED if .East in t else {0}

ret[.South] = NORTH_CONNECTED if .South in t else {0}

ret[.West] = EAST_CONNECTED if .West in t else {0}

ret[.Top] = BOTTOM_CONNECTED if .Top in t else {0}

ret[.Bottom] = TOP_CONNECTED if .Bottom in t else {0}

case Air:

ret[.North] = SOUTH_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.East] = WEST_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.South] = NORTH_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.West] = EAST_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.Top] = BOTTOM_NOT_CONNECTED

ret[.Bottom] = TOP_NOT_CONNECTED

case:

ret = ~{}

}

return

}

grid_propagate :: proc(grid: ^Grid) -> bool {

// Update candidates based on cells

for z in 0..<GRID_SIZE do for y in 0..<GRID_SIZE do for x in 0..<GRID_SIZE {

cell := grid.cells[x][y][z]

tc := tile_connections(cell)

// North

if y < GRID_SIZE - 1 do grid.candidates[x][y + 1][z] &= tc[.North]

// East

if x < GRID_SIZE - 1 do grid.candidates[x + 1][y][z] &= tc[.East]

// Top

if z < GRID_SIZE - 1 do grid.candidates[x][y][z + 1] &= tc[.Top]

// South

if y > 0 do grid.candidates[x][y - 1][z] &= tc[.South]

// West

if x > 0 do grid.candidates[x - 1][y][z] &= tc[.West]

// Bottom

if z > 0 do grid.candidates[x][y][z - 1] &= tc[.Bottom]

// if cell is a tile, make sure it is not a candidate anywhere else.

if tile, ok := cell.(Tile); ok {

cand := Candidates{ int ( transmute(u8)tile ) }

grid.candidates -= cand

grid.candidates[x][y][z] = cand

}

}

any_collapsed := false

// Update cells based on candidates

for z in 0..<GRID_SIZE do for y in 0..<GRID_SIZE do for x in 0..<GRID_SIZE {

cand := grid.candidates[x][y][z]

if cand == {} do return false // illegal state reached

// COLLAPSE

// obviously only a new collapse if it isnt collapsed already

if grid.cells[x][y][z] == nil && card(cand) == 1 do for id in cand {

any_collapsed = true

// What did actually collapse

grid.cells[x][y][z] = Air{} if id == 0 else transmute(Tile)i8(id)

}

}

success := true

if any_collapsed do success = grid_propagate(grid)

return success

}

grid_init :: proc (grid: ^Grid) {

// different grid_init from before to reuse memory

grid.cells = {}

grid.cells[MID_POINT][MID_POINT][MID_POINT] = ~Tile{}

grid.candidates = ~Candidates{}

grid_propagate(grid)

return

}

grid_controlled_demolition :: proc(grid: ^Grid) -> bool {

// all the shuffling

rows := [GRID_SIZE]int{}

for i in 0..<GRID_SIZE do rows[i] = i

cols := rows

verts := cols

rand.shuffle(rows[:])

rand.shuffle(cols[:])

rand.shuffle(verts[:])

ids := []int{ 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63 }

rand.shuffle(ids)

// target collapse stored here

t_x, t_y, t_z: int

// tracking the minimum

min_card := max(int)

for z in verts do for y in cols do for x in rows {

c := card(grid.candidates[x][y][z])

(c > 1) or_continue // already collapsed

if c < min_card {

t_x = x

t_y = y

t_z = z

min_card = c

}

if min_card == 2 do break // no point in looking further in this case.

}

for id in ids do if id in grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] {

// COLLAPSE

if id == 0 {

grid.cells[t_x][t_y][t_z] = Air{}

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] = {0}

} else {

tile := transmute(Tile)i8(id)

cand := Candidates{ id }

grid.cells[t_x][t_y][t_z] = tile

grid.candidates -= cand

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] = cand

}

break

}

return grid_propagate(grid)

}

main :: proc () {

grid := new(Grid)

grid_init(grid)

outer: for i in 1 ..< max(int) {

for grid_controlled_demolition(grid) {

if grid.candidates[0][0][0] == {0} do break outer

}

grid_init(grid)

if i % 10 == 0 do fmt.eprint("try", i, "\r")

}

for z in 0..<GRID_SIZE do for y in 0..<GRID_SIZE do for x in 0..<GRID_SIZE {

fmt.println(x, y, z, grid.candidates[x][y][z])

}

}

Running this takes forever, by the way. Even when compiling it optimized for speed with odin build . -o:speed, the first run at the solution took more than 290,000 iterations and more than 18 minutes before I gave up on it, and decided to change allocations a bit. Doubt rised in my heart whether this halts at all, or if it has a nasty bug that is difficult to find due to, well, the long runtime. Threading will probably not make this faster.

The longest time I ran it, it went for 25,771,590 iterations and around 27 hours of usertime before I shut it off.

Maybe, just maybe, completely random attempts are the wrong approach. Maybe I actually need to implement proper backtracking to ensure that the same tree is not being barked multiple times.

I have spent a few days mulling it over, and the simplest way to implement is to have a dynamic array in Grid to save every state where an arbitrary (not random) choice was made, in addition to the index of the choice. And whenever reaching an illegal state, the grid is reset to the previous state, and the index is incremented. Should the index reach a certain value (10 or whatever), then the last state is discarded and the index is incremented on the one before it.

Grid Enhancements

So, first things first, here is the new Grid struct, with a few type aliases to lighten the mood.

Cell_Grid :: [GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE]Cell

Candidate_Grid :: [GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE][GRID_SIZE]Candidates

Demolition_Point :: struct {

grid: Cell_Grid,

idx: int,

}

Grid :: struct {

cells: Cell_Grid,

candidates: Candidate_Grid,

demolitions: [dynamic]Demolition_Point

}

Having the dynamic array there should, in theory, be safe. The Grid is initialized once, And whenever the controlled demolition fails, the index of the last item in demolitions is updated. Or, if it exceeds some threshold (preferably exhausting all the candidates in a cell), the last entry is removed and the second to last entry increments its index instead.

Now, for the procedures used, grid_propagate should probably be the same. While grid_init and grid_controlled_demolition should perhaps be overhauled.

A potential enhancement, to avoid the algorithm being stuck on the same start every time, is to reuse the shuffling above in initialization. Shuffling the IDs for every new Demolition_Point would be enough, unlike shuffling rows and columns. the reason for that is, if the program exhausted every candidate from a cell, then there is no point in trying other cells from the same state. This is what that would look like.

Demolition_Point :: struct {

grid: Cell_Grid,

idx: int,

ids_shuffle: [64]int

}

// ...

grid_init :: proc (grid: ^Grid) {

grid.cells[MID_POINT][MID_POINT][MID_POINT] = ~Tile{}

grid.candidates = ~Candidates{}

grid_propagate(grid)

start_point := Demolition_Point {

grid = grid.cells,

idx = 0,

ids_shuffle = IDS, // IDS is numbers from 0 to 63.

}

rand.shuffle(start_point.ids_shuffle[:])

append(&grid.demolitions, start_point)

return

}

Demolition Revision

Previously, grid_init was used to reset the state after every failed attempt. This time a different procedure is needed, which may be called grid_backtrack, or increment, who knows. This proc would only be called for a failed controlled demolition. Demolition can fail for two reasons: either the candidate chosen forced an illegal state, or all candidates from the lowest cell were exhausted. This call for an enum! grid_controlled_demolition can return this enum and based on whivh grid_backtrack decides what to do.

Demolition_Result :: enum { Success, Exhausted_Candidates, Illegal_State }

And this would be the new version of grid_controlled_demolition, with less shuffling and small changes:

grid_controlled_demolition :: proc(grid: ^Grid) -> Demolition_Result {

t_x, t_y, t_z: int

min_card := max(int)

for z in RANKS do for y in RANKS do for x in RANKS { // RANKS is numbers 0 to 30

c := card(grid.candidates[x][y][z])

(c > 1) or_continue

if c < min_card {

t_x = x

t_y = y

t_z = z

min_card = c

}

if min_card == 2 do break

}

demo_pt := grid.demolitions[len(grid.demolitions) - 1] // should never be empty

counter := 0

exhausted := true

for id in demo_pt.ids_shuffle do if id in grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] {

if counter < demo_pt.idx {

// Skip till idx is reached.

counter += 1

continue

}

// COLLAPSE

if id == 0 {

grid.cells[t_x][t_y][t_z] = Air{}

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] = {0}

} else {

tile := transmute(Tile)i8(id)

cand := Candidates{ id }

grid.cells[t_x][t_y][t_z] = tile

grid.candidates -= cand

grid.candidates[t_x][t_y][t_z] = cand

}

exhausted = false

break

}

// Here is the interesting part.

if exhausted do return .Exhausted_Candidates

ok := grid_propagate(grid)

return .Success if ok else .Illegal_State

}

The Main Loop

Before figuring out how the supposed grid_backtrack looks like, it might help to construct how the loop looks. With a side of Odin flavoured golf:

main :: proc () {

grid := new(Grid)

grid_init(grid)

// inner tag is only for readability

outer: for i in 1 ..< max(int) do inner: for {

result := grid_controlled_demolition(grid)

switch result {

case .Success:

if grid.candidates[0][0][0] == {0} do break outer

demo_pt := Demolition_Point {

grid = grid.cells,

idx = 0,

ids_shuffle = IDS

}

rand.shuffle(demo_pt.ids_shuffle[:])

append(&grid.demolitions, demo_pt)

case .Exhausted_Candidates, .Illegal_State:

grid_backtrack(grid, result)

if i % 10 == 0 do fmt.eprint("try", i, "\r") // debug land

break inner

}

}

grid_draw(grid) // <-- later

}

The Step Back

For backtracking, what is done depends on the error returned. If it is an illegal state, just increment the index and restart. If it is exhausted candidates, remove the last state, then increment the index of the previous one. This is the initial idea:

grid_backtrack :: proc (grid: ^Grid, result: Result) {

switch result {

case .Success:

unreachable()

case .Exhausted_Candidates:

pop(&grid.demolitions)

case .Illegal_State:

// nothing

}

last := slice.last_ptr(grid.demolitions[:])

last.idx += 1

grid.cells = last.grid

grid_propagate(grid)

}

Unfortunately, putting all these together and running it, quickly hits a segfault. I could not figure out why at first, but then peppering a few fmt.eprint around, I realized that the state of grid.candidates wasn't being reset properly between iterations. So any changes made to it in grid_propagate would persist.

I fixed that by adding a line just before the call to grid_propagate in grid_backtrack:

grid.cells = last.grid

grid.candidates = ~Candidates{} // <-- this one

grid_propagate(grid)

Ok, not segfaulting. Good news. The peppered around fmt.eprints show behaviour that make sense.

Also, similarly to the reset the world behaviour experimented with at first, this is still taking a long time to run, with no idea whether it halts or not. Building it with -o:speed as done before, and running it overnight might give the needed answer.

Out of Memory

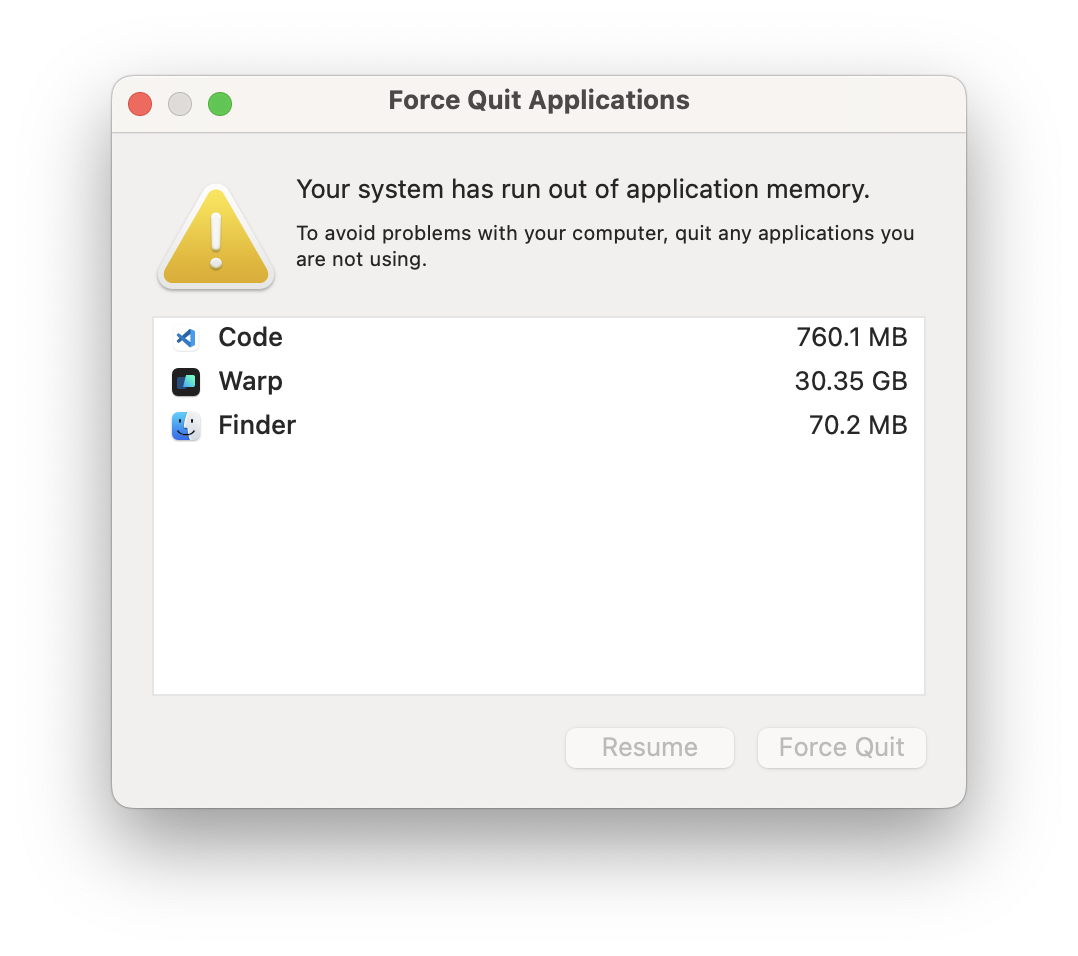

I woke up to this:

I spent a few days trying different things out and seeing what is causing the ballooning in memory. For whatever reason, the program seemed to be allocating a lot more memory than I expected, and the dynamic array of demolitions is ballooning uncontrollably. In theory, there would be 31x31x31 successful demolitions at most. I tested this by using Odin's core library's Small_Array, which is a "dynamic" array with a fixed capacity, giving it 31x31x31 size, and it quickly filled up and panicked as it attempted appending to a full array. This indicates, to me, a logic error somewhere.

I tried different variations of the main loop, including inlining grid_backtrack. I removed the ID shuffling per Demolition_Point. I made the Grid smaller. I tried not shuffling IDS. All of them either ran into the same memory issue or just .. kept running.9 I am at a complete loss of what the issue might be. Clearly this approach to backtracking is not working. I am honestly out of spoons thinking about this.

Giving Up and Lessons Learned

To be honest, it has been almost two months since I started this article, and I am tired of iterating on the problem. Frankenstein's Monster works in theory, given infintie time, and for now this is enough for me. Maybe one day I will go back to figuring how to get to a slution in human time.

The part I enjoyed the most was iterating on the graphics with raylib. The library is really easy to use, if not as flexible as I hoped. Maybe for the next project I will do some sort of game, or just use it as generative art.

I should watch more Coding Train videos.